And it still isn't easy. A staging of The Ring remains the biggest challenge for any opera company and one of the biggest challenges in the theatre. Wagner decided that the only way to stage his work satisfactorily was to build a new theatre. He settled in the town of Bayreuth in northern Bavaria, and with the financial support of King Ludwig, a huge (and impressionable) Wagner fan, built his theatre. And so, the Bayreuth Festival, which is run every summer by a member of the Wagner family and which only performs the operas of Richard Wagner, was born.

| |||

| The Rhinemaidens at the Bayreuth premier, 1876 |

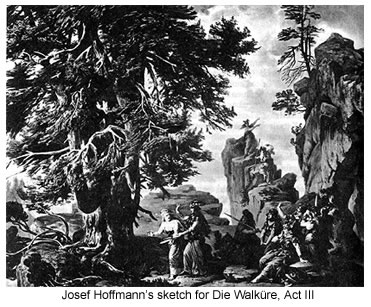

The scenery for that first production was by Joseph Hoffmann. It was pictorial and literal and the designs were used for many years (and influenced subsequent productions). A record of "Wagner rehearsing The Ring" survives in an eye-witness account by Heinrich Porges and there are several illustrations of the Hoffmann sets.

|

| Das Rheingold |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Die Walkure, Act 1 |

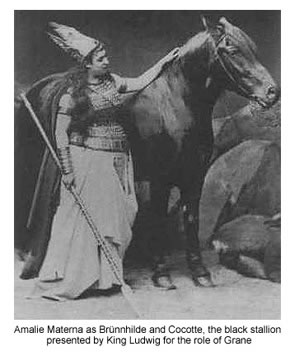

Hoffmann was a landscape artist; his designs were modified to make workable sets. But his basic layout of scenes would remain almost unchanged for over 50 years. Carl Dopler designed the costumes, and with his designs for Brunnhilde, created an opera stereotype that would last more than a century.

While Wagner's widow, Cosima, preserved The Master's productions in amber, even down to the movements of the singers' hands and heads, elsewhere there was a minor revolution in the theatre and two powerful forces emerged at the turn of the century. Until that point, theatre and opera production was largely in the hands of the author/composer/conductor/leading actor, but at Moscow's Arts Theatre, Constantin Stanislavski was helping to create a new role: the theatre director. And the theatre director now had an additional, vital weapon to add to his stagecraft armoury: electric lighting.

There were some who realised the power of electric lighting before others. One of theatre's design pioneers (whose designs were often too far forward thinking that they never made it to the stage) was Adolphe Appia (1862-1928).

While Hoffmann's designs consisted largely of painted scenery with perspective backdrops and side cloths or flats (important for hiding and hanging lighting equipment), Appia's designs were much less literal and much more solid. He believed that, like the actors who'd inhabit them, his sets should be three-dimensional, so his stage designs had not only width and depth, but height too.

|

| Appia's design for Walkure Act 3 (compare with Hoffmann's) |

| |||

| Appia's design for Parsifal |

The practicalities of bulkier sets often meant that they became less pictorial and more abstract: perspective backdrops and pretty scenery would detract from the very real and three dimensional actors and structures. Advances in stage lighting meant that Appia could use and manipulate the lighting to give the actors and stage a depth and form through light and shadow, rather than through painting. And in removing the actor from a painted cloth, the actor did not have to struggle to stand out; he could seem much more to inhabit the world created on stage, than merely look as if he were standing in front of a picture. Appia was influential on another designer/director, Edward Gordon Craig: between them, their ideas and designs would have a huge impact on the Bayreuth Festival when it was run after the Second World War by Wagner's grandsons, Wieland (especially) and Wolfgang.

|

| Appia's design for Tristan und Isolde |

|

| Appia's Sketch for a Wagner opera |

| ||

| Gordon Craig's design for Hamlet |

Hitler loved Wagner's music, and during the war, the Bayreuth Festival became closely linked with the Nazi regime. After the war, the long process of self-examination and cleaning began, not only for the Festival but for Germany and Europe as a whole. Clearly the war and its origins and aftermath needed to be explored, not just through personal thought or public politics, but in art and culture as well. Re-opening the Festival in 1951, Wieland Wagner sought to break away from earlier Festivals, introducing a new approach to design and presentation (often referred to as New Bayreuth): Hoffmann was out; Appia was in. And Wieland, as stage director, was in charge.

Here is a picture of Wieland's 1951 Ring cycle when the Festival re-opened after the war: the end of Siegfried, which takes place on the Walkure rock seen above at the end of Walkure in designs by Hoffmann and Appia above

It's sparser than Appia. The backdrop gives some suggestion of clouds/sky. But more importantly, it's a three dimensional space, with both actors well-lit but not exaggeratedly so. Although we don't know where we are (we are simply "somewhere"), the space is clearly solid and real, not painted and artificial. What is most crucial though, is that Wagner's stage description here asks for "a visible mountain-top... downstage, a pine tree": these are gone. In New Bayreuth, Wagner's stage descriptions and stage directions can be ignored. The era of Regie (or Director) Theatre in the opera world has truly begun.

If there is one issue which seems to be the most divisive among opera goers, it is the idea of Regie opera: that a director will change the librettist/composer's ideas, seemingly at will. Operas are updated, locations changed; sex and violence are thrown into the mix when they were not originally there; productions become "ugly". Regie detractors say that the operas are unrecognisable; that the directors are acting against the composer's wishes; that the directors are putting themselves first and imposing a vision, rather than putting the work first; that regie theatre is more physically challenging, so singers are cast more for their appearance than their voice; that regie opera is confusing and will deter newcomers from attending the opera. Conversely, regie supporters often say that revitalising the standard repertoire with new presentations not only keeps the work fresh and stimulating for regular opera goers, but also helps to attract new and younger audiences. They suggest that a fresh perspective helps both audience and performer approach the work in new ways and find resonances that may have previously been overlooked; that there's more to opera than "pretty pictures" and that maintaining a "traditional" production style is both untheatrical and will lead to stagnation.

This is a large topic and I'll probably come back to it again in future posts. Among directors often associated with regie theatre in opera are Robert Wilson, Richard Jones, Calixto Bieito, Stefan Herheim, Christoph Marthaler, Christopher Alden, David Alden, Peter Konwitschny, Dmitri Tcherniakov, Krzysztof Warlikowski, Claus Guth and Peter Sellars.

To some, regie theatre means the death of opera; to others, it's the best way of keeping it fresh and alive.

Either way, it seems pretty much here to stay.

Fascinating - made me think again about relationship of director and playwright in theatre - and also coincided with me telling a friend that the lighting designers of the Olympics Opening Ceremony were unsung heroes. Presumably the analysis goes beyond Wagner- recent opera I have seen seems to be drawing more on wider theatrical developments.

ReplyDeleteRegie opera is not limited to Wagner though as many of his operas have mythical subjects where time and place seem less important than in some other operas, his works seem to be more regularly re-staged than most others. Considering the often spectacular nature of some opera and the demands of playing operas in alternating repertory, many opera houses are among the most technically advanced of all theatres. Yes, lighting design is probably something we take for granted now: certainly the expectations of lighting design at such outdoor events and rock concerts is very high. A bigger question might be: should the lighting design draw attention to itself? If not, should the stage design? Or the director? Or the performer?

DeleteGoing slightly off topic but still on subject of lighting. I remember an art exhibition I went to years ago that recreated the type of light that artists had when they were painting and displaying their masterpieces(talking Rembrandt and Van Gogh)Completely changed the way I looked at art.

ReplyDeleteThank you. Glad I finally read it all the way through. I wouldn't think myself a regie supporter as I tend to hate when most things are remade. I guess the Faust productions I have may be considered regie? They were good. Still I would love to see a version of the original production.

ReplyDeleteThe stage and lighting of The Met's Ring cycle was certainly a large part of the production. It was quite a visual treat.